New Approaches to the Future of Urban Highways

By Zeke Mermell, AICP, LEED AP, Senior Urban Designer

Since World War II, the federal government has vastly funded roads and highways over transit, cycling and walking. The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 may be the epitome of this imbalance but, as recently as 2020, the majority of transportation grants were for roads. Without sufficient community input or consent, highways bisected neighborhoods in cities from coast to coast beginning in the 1930s-40s, displacing residents, disrupting connectivity to jobs, food, and medical care, and lowering land values. Affected communities, disproportionately home to low-income people and people of color, continue to be impacted by air and noise pollution as highways persist as barriers to opportunity.

The continued prioritization of highways over transit and sustainable mobility amounts to a form of climate denialism. With transportation now the leading source of emissions in the US (and one of the only areas where emissions are growing), reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) is essential to mitigating the worst impacts of climate change. Reducing the footprint of our highway network can reverse the cycle of expanded roadways supporting sprawling land uses and increased driving, thereby reducing motor vehicle trips and shifting trips to more sustainable modes.

The policy landscape is changing. Cities as varied as Seattle and Niagara Falls, NY, have removed, shrunk, or covered over highways. In a rare intervention, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) recently asked the Texas Department of Transportation to halt expansion of I-45, dubbed the North Houston Highway Improvement Project, citing civil rights and environmental justice concerns raised by local groups like Stop TxDOT I-45. NHHIP would result in the demolition of significant cultural institutions, as well as one of Houston’s oldest public housing facilities.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA, the passed Infrastructure Bill) goes even further. IIJA includes the Reconnecting Communities pilot program, which dedicates $1 billion (over the course of 5 years) in planning and capital construction funding for reconnecting (via removal or mitigation) neighborhoods cut by highways or other transportation infrastructure. Criteria for projects applying for Reconnecting Communities program funding include addressing design factors such as high speeds and grade separation.

The Build Back Better (BBB) Act passed by the US House of Representatives (but currently stalled in the legislative process) includes the Neighborhood Access and Equity Grant Program, which would mitigate highway impacts in underserved communities and dedicate $4 billion for removing, remediating, replacing, or capping highways via FHWA competitive grants. It would also encourage projects to promote sustainability and resilience: reducing air pollution and greenhouse gas, managing stormwater runoff and flood risk, and mitigating heat islands and tree canopy gaps. Grant funding would have an equity focus, going to projects designed to prevent displacement, employ local residents, and encourage public participation.

Design options

Moving beyond past policies involves rethinking the steps that led to urban highways’ harms. For instance, Vehicle Level of Service (LOS) measures a street’s capacity to move motor vehicles. Giving primacy to the movement of vehicles with as little delay as possible in decision-making processes can encourage more automobile-based travel and comes at the expense of cleaner, healthier, more affordable modes.

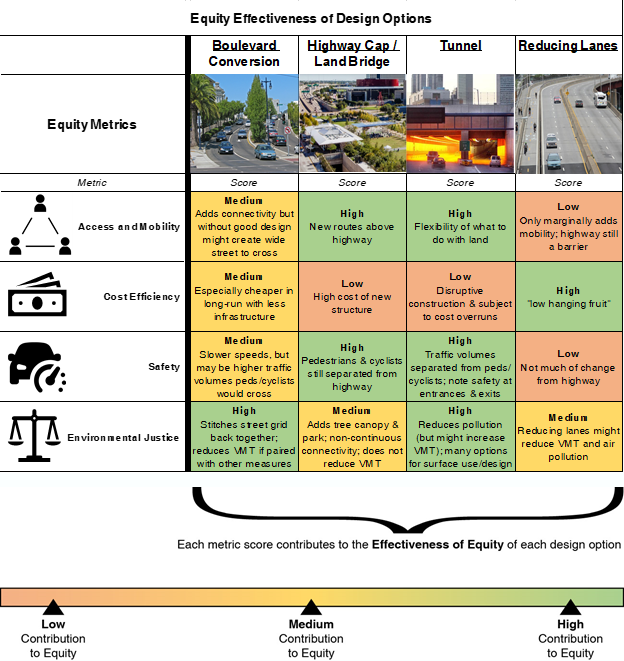

There is an urgent need to shift to metrics that prioritize access and mobility for all users, long-term cost-efficiency, safety, and environmental justice. The four design options discussed and illustrated in the comparative table below are a selection of potential solutions. These options respond to different levels of effectiveness for each equity metric. The table can help determine if an option is best suited for a particular project.

Boulevard conversion

Converting highways into boulevards (or walkable/bikeable streets) is a frequent solution to the barrier effect of a highway. Without an elevated or depressed barrier, neighborhoods can be stitched back together, helping residents cross a corridor more safely.

Boulevard conversion in of itself is not a panacea. Consideration should be given to the overall roadway width to ensure safe crossing. Furthermore, moving high traffic volumes to the surface level might present safety and mobility challenges for crossing pedestrians and cyclists. The Congress for the New Urbanism, with a longstanding campaign on boulevard conversion, defines it as designing “well-proportioned sidewalks, frequent and well-signed crossings, street trees, and one or more medians that create a desirable and walkable avenue.” Boulevard conversion can reduce VMT if paired with other measures. Motorists might shift travel modes (or not) depending on alternative highway routes made available, lane reduction or changes to convenience along the route, or paired transit or cycling improvements.

Grassroots campaigns for boulevard conversions are active nationwide, including the Claiborne Expressway (New Orleans, LA) and I-81 (Syracuse, NY). Both of these highways were cited in a 2021 White House briefing room statement as examples of how to redress historic inequities.

Highway caps and land bridges

Highway caps, decks, lids, and land bridges all involve constructing a surface above a highway. Caps address environmental justice by increasing communities’ access to jobs, education, recreation, and other opportunities, by limiting surrounding air and noise pollution, and (when taking the form of parks) by filling gaps in open space access. However, caps do not reduce highway space or VMT.

Caps could also address housing shortages. A Seattle report on a proposed cap estimated that 4,500 new housing units, many affordable, could be constructed by capping and building on top of Interstate 5. Like boulevard conversions, highway caps also reconnect neighborhoods scarred by highways by reconnecting city blocks with walkable and bikeable routes. However, the connection is non-continuous since the highway is a barrier beyond the cap location.

Tunneling

Placing a highway into a tunnel is another way to stitch communities back together, albeit a costly one. Boston’s Central Artery (the “Big Dig”) and Seattle’s Alaskan Way are two prominent examples that added open space and development while not removing the highway itself. Since highway volumes are separated by the tunnel from pedestrians and cyclists, it is typically safer than a surface boulevard; however, attention must be made to the design at a tunnel’s on/off ramps as infrastructure could mimic highways to a certain extent.

Tunneling arguably might increase VMT. Tunnels make automobile travel easier, bypassing complexities of an at-grade or above-ground urban travel and thus reducing congestion at first. This induces demand and as shown in places like Boston, congestion reappears as automobile travel is encouraged. Tunneling can however score high for environmental justice, since there is much flexibility with transforming space where a highway used to be, and its pollution is not as impactful on the surrounding environs.

Reducing lanes

“Rightsizing” a highway by reducing lanes keeps most infrastructure in place. This can be done if the roadway’s capacity exceeds traffic volumes and can also serve as a proactive approach, as reducing lanes potentially reverses induced demand (sometimes called “traffic evaporation”), VMT, and air pollution. This may also allow for space to be reallocated back to other transportation modes or community uses, furthering environmental justice.

Also, extraneous on- and off-ramps can be shifted to “rightsize” a corridor or interchange footprint. Routing efficiencies or a decreased need for ramps built during higher traffic volumes can yield space in urban communities for economic development, open space or civic uses.

Conclusion

The significant increase in funding for urban highway mitigation from IIJA and potentially BBB presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity for a reimagining of urban highways, whether they are elevated, submerged, or at surface grade. As illustrated above, there are numerous opportunities to ameliorate past decisions that harmed disadvantaged communities and expand multi-modal options while accommodating essential regional through traffic.

Cities and states can evaluate whether changes in their highways are warranted by evaluating the effectiveness of options based on the above metrics: access, cost efficiency, safety, and environmental justice. Forecasting and modeling these metrics can include, for example, projecting the reduction of air and noise pollution along a project corridor. Design options can be weighed in terms of reduction of health risks such as asthma, especially for vulnerable populations.

The Inner Loop North project in Rochester, NY, provides an example of how racial equity metrics may be applied to highway removal. Since the 1950s, the Inner Loop has disconnected neighborhoods. Its east segment was converted into a complete street in 2017, but racial equity was not a focus. The next segment is being planned with attention to equity.

Each design option for Inner Loop North must utilize a racial equity lens and demonstrate engagement with residents of all races, abilities and backgrounds. The design team must note each option’s quality-of-life impact, including access to jobs, goods and services in the region; city services; and the potential of unintended consequences on racial equity. Each option must be viewed through its impacts on the environment, youth services, accessibility, and other metrics.

New approaches to our urban highways, focused on addressing equity at the local level, are possible with the passage of landmark federal legislation. This includes providing automobile free mobility options for residents and giving reprieve to communities that bear the inequitable impacts of highways. A new future for urban highways is ahead.