The Path to Permanent Open Streets

By Colin Brown, Transportation Planner

Over the past year and a half, the role of streets in cities and towns across the country has evolved substantially. Communities have rediscovered the potential of this shared space as a place for gathering, exercising, dining, and more. What had become, in many cities, a public asset occupied solely by cars, is now being viewed with an eye towards more flexible uses that can bring added value to local communities.

The ‘Open Street’ has become one of the most widespread and popular transformations of the public right-of-way. Generally speaking, open streets restrict vehicular access to streets—or portions of them—during certain days and times, allowing pedestrians, people on bikes, and other micromobility users to safely make use of the roadway. In addition to allowing protected corridors for active transportation, this model provides local residents a communal space for shared activities—something often overlooked in neighborhoods lacking access to open space.

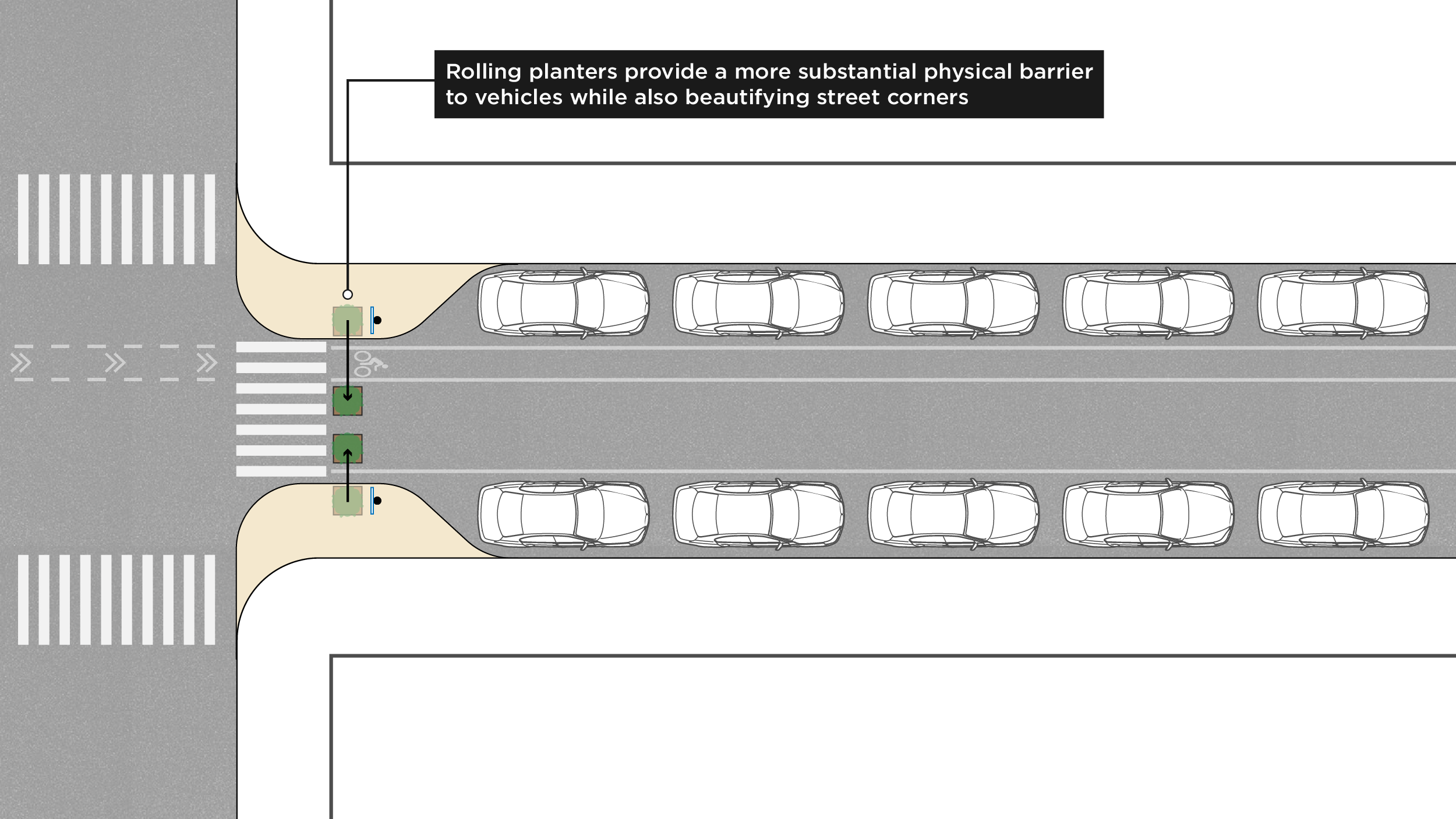

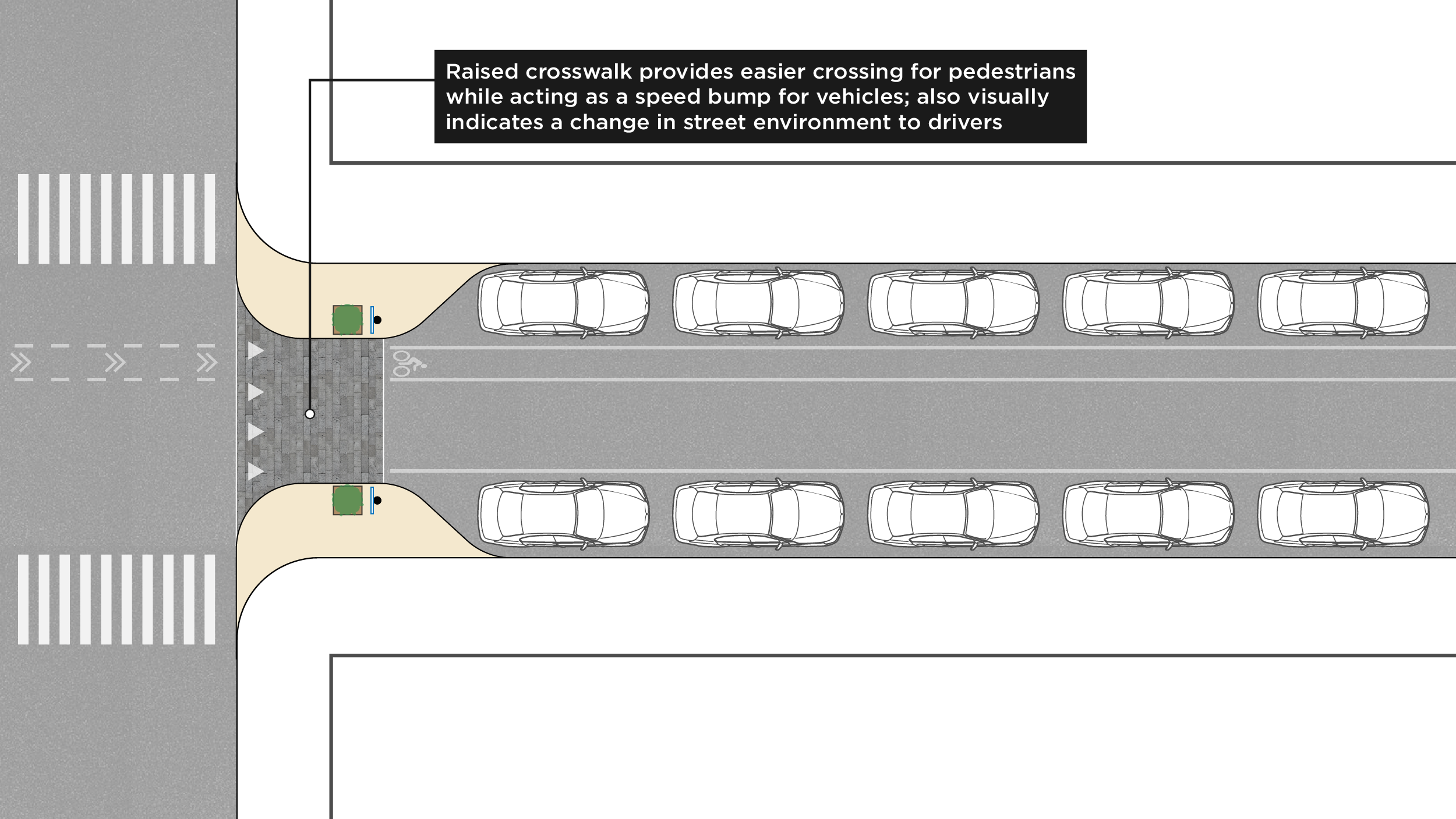

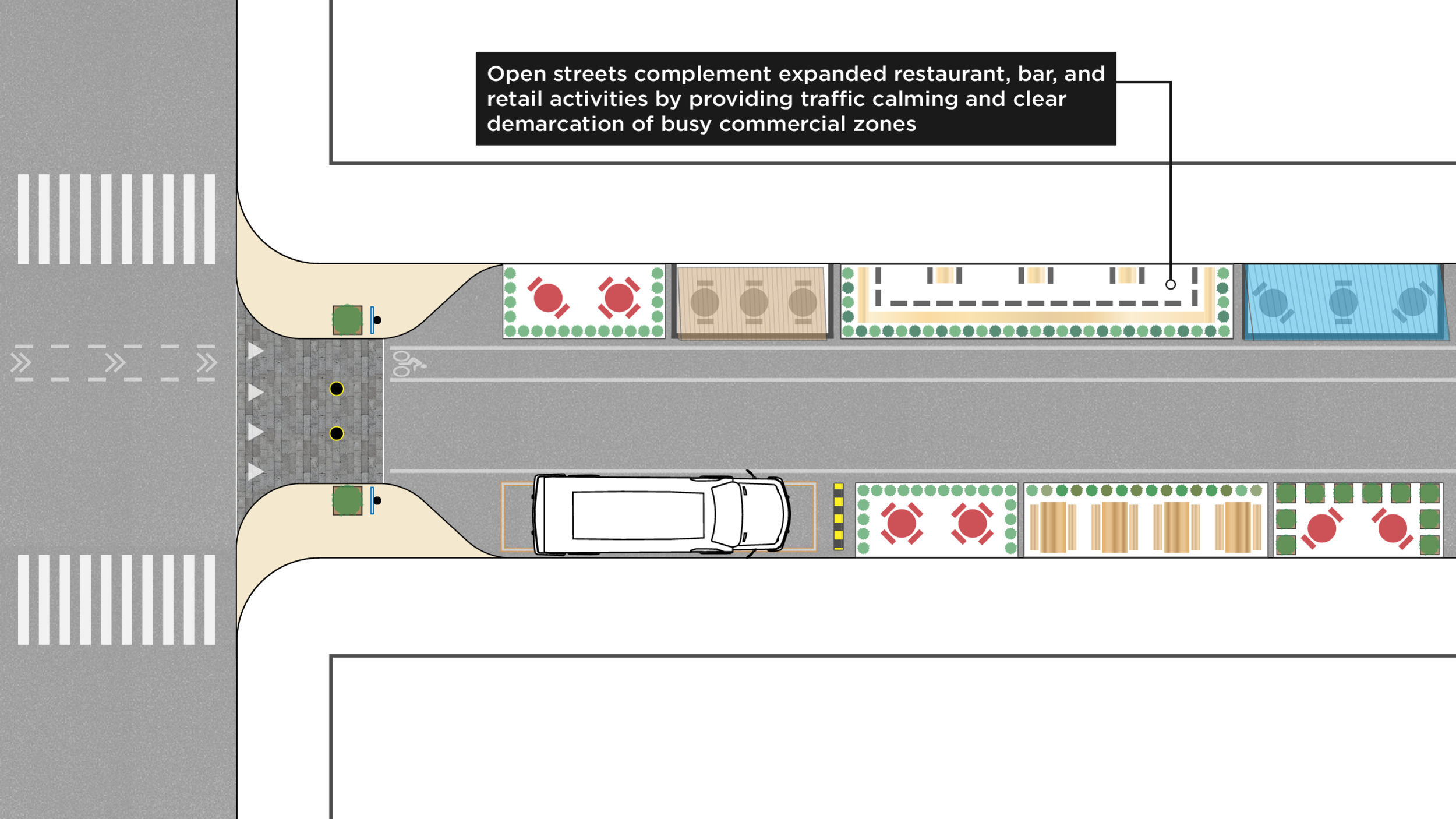

Above: two permanent design ideas for an Open Street near Sam Schwartz’s New York office.

While there will never be full agreement among community members about policy decisions, open streets programs across the country have proved to be among the most popular public initiatives in response to the pandemic. This has resulted in mayors—including in New York City, home to the largest such program—formally incorporating open streets as permanent features.

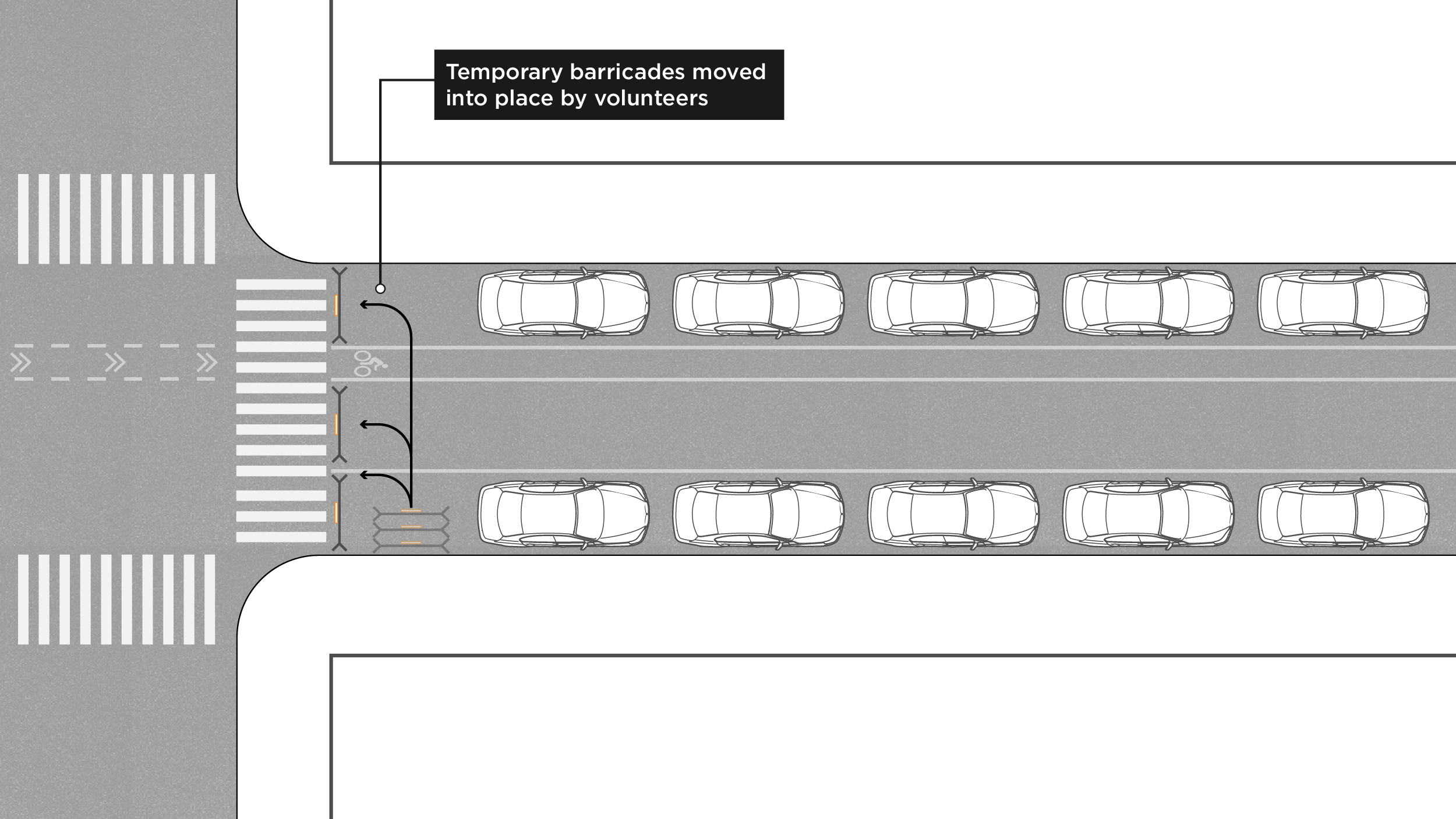

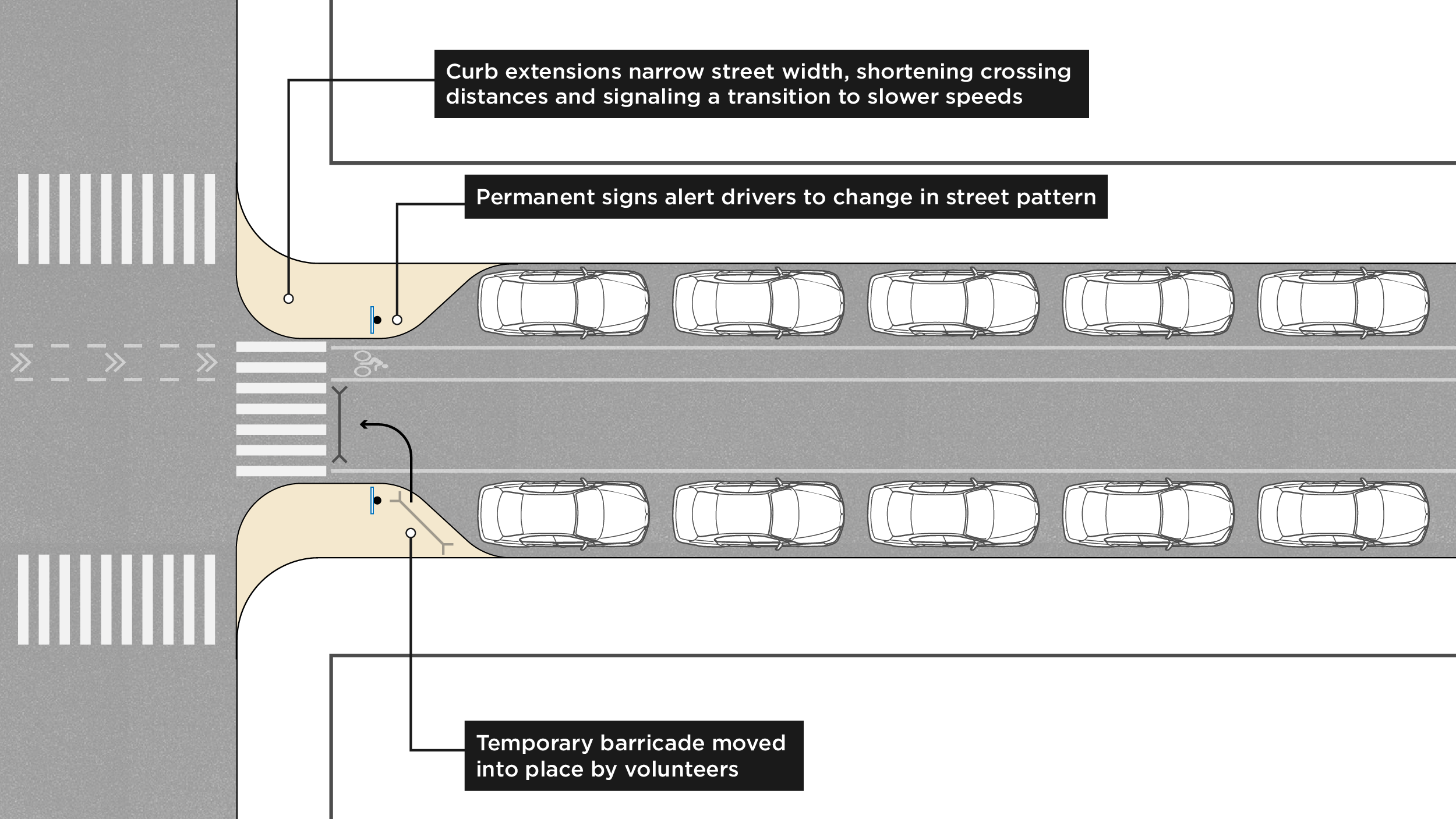

Now that we know open streets are here to stay, what’s next? The temporary cones, barricades, and signs that have been used by community volunteers over the past 18 months to alert road users to new conditions have a number of flaws. These makeshift methods, while somewhat effective, lack the permanence and consistency needed for city-wide programs. Relying on volunteers to administer barricades on a daily basis—although beneficial in a community-building respect—is unsustainable in the long run. Similarly, depending exclusively on traffic enforcement to ensure driver adherence to regulations is a costly and problematic proposition.

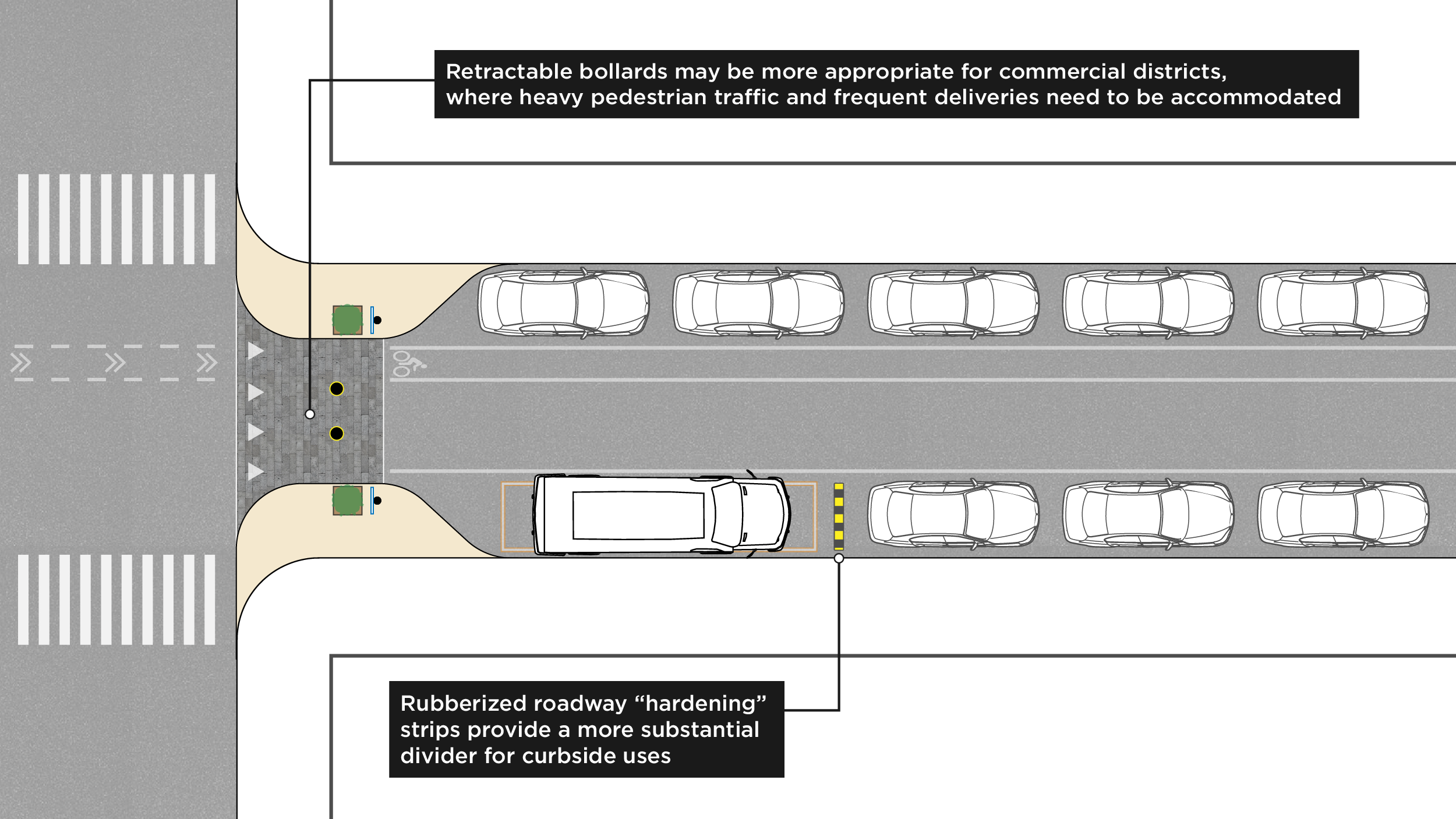

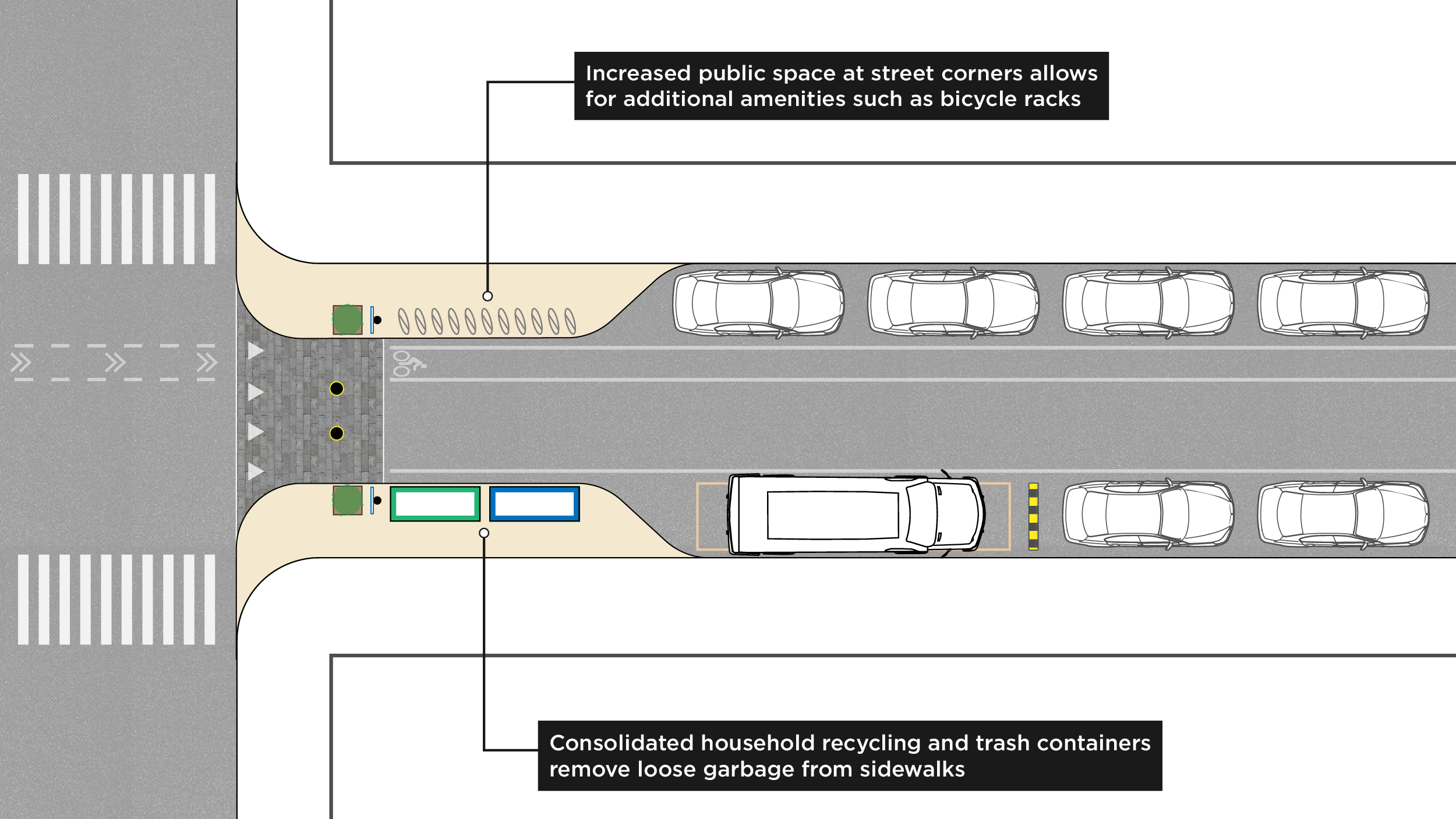

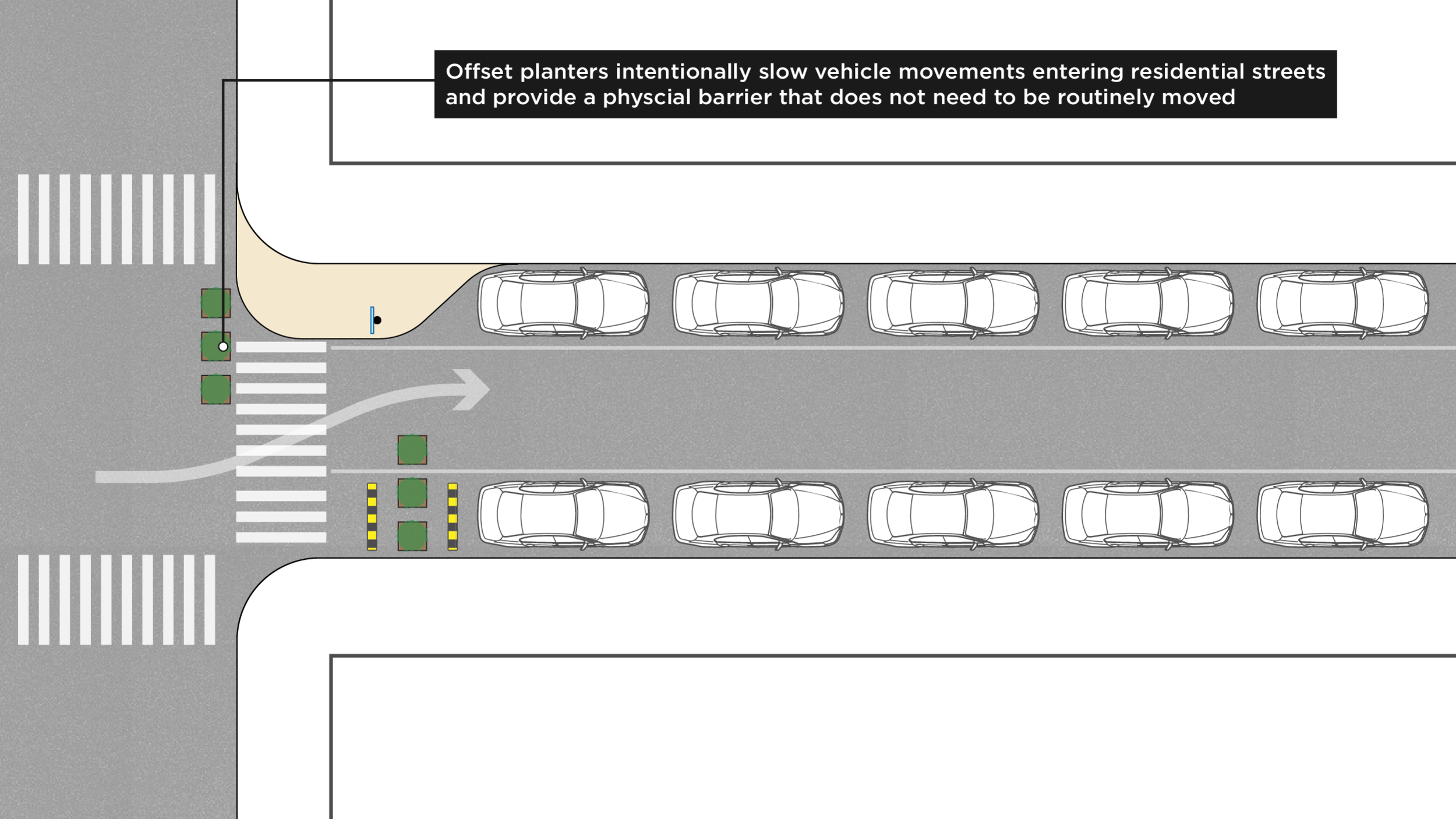

Street design changes are needed to formalize open streets programs and better integrate them with local concerns. These designs should aim to manage vehicle traffic in predictable ways, primarily through passive configurations that require less day-to-day volunteer input and attention.

While more permanent physical elements are needed, design changes should not be over-engineered or burdened by drawn-out bureaucratic processes. A toolkit of inexpensive, but durable, street fixtures would provide city agencies with the flexibility to address a number of roadway conditions. With existing buy-in from local communities, residents should be consulted on the appropriate configurations for nearby open streets.

Above: Design tactics for making an Open Street permanent.

The benefits of a permanent open streets program extend to both residents and public agencies. Because design interventions for open streets focus on intersections or the “gateways” to streets, they can be accomplished with minimal impact to on-street parking—often a contentious issue that can delay projects for years. Once implemented, the re-configured street space at corners provides improved safety for all road users, even when the adjacent open street is not in effect. As an added bonus, the reclaimed pavement provides an opportunity to add amenities that would otherwise not have sufficient space to exist in a neighborhood, especially where sidewalk space is in high demand.

Beyond specific design considerations, cities need to have an overall vision for what objectives their open streets programs are aiming to achieve. These programs can be an important tool in addressing the inequitable distribution of open space in cities, as a complementary element to traditional parks and other green spaces. Open streets should also be viewed in the framework of active mobility—they share many of the same design aspects of “bike boulevards” and ought to be included in the planning of low-stress, low-carbon transportation networks. Finally, permanent open street programs—equipped with sufficient design interventions—align closely with Vision Zero and other safety goals set by municipalities across the country.

If public agencies are serious about the safety of the most vulnerable road users in their communities—children, the elderly, people with disabilities, pedestrians, and those on bikes—it would be hard to create a program as responsive and flexible as the growing movement of open streets. It’s time to formally integrate these programs into wider transportation and open space strategies in order to realize their benefits on a city-wide scale.